TennCare has released a draft of its opening bid in negotiations with federal regulators over a Medicaid block grant. (1) The proposal includes three key components:

- A broad set of administrative and benefit design flexibilities that Tennessee could tap without prior federal approval or oversight.

- An allotment to replace current federal funding for a portion of TennCare costs.

- The opportunity to keep (without a state match requirement) half of any savings from spending less than the full allotment.

This brief asks (and attempts to answer) seven questions to help stakeholders understand the details of the proposal and what it could mean for TennCare enrollees and providers and the state’s budget.

Editor’s Note: TennCare officially sent a revised draft of this proposal to federal regulators in November 2019. Read What’s in Tennessee’s Medicaid Block Grant Request? for Sycamore’s most up-to-date analysis.

Key Takeaways

- The plan would give Tennessee policymakers unprecedented control over changes to optional program benefits and provider payments without federal approval or oversight.

- The state would also shoulder some additional long-term financial risk under this plan, but overall the proposed funding changes are weighted heavily in Tennessee’s favor.

- This broad shift in power from federal to state policymakers could have significant effects on TennCare spending, enrollees, and providers — either positive, negative, or mixed depending on if and how current or future state officials use that power.

1. Why is TennCare proposing this?

Earlier this year, the General Assembly passed legislation requiring TennCare submit a request to the federal government to convert the state’s Medicaid funding into a block grant. It established a November deadline for submission to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and included broad parameters for how the block grant should work. (2)

2. What flexibilities are in the proposal?

The draft waiver proposes a broad set of benefit design and administrative flexibilities that Tennessee could tap without prior federal approval or oversight. Federal approval processes are largely in place to ensure transparency, set goals and parameters, and evaluate and monitor the effects of changes on enrollees. (3) (4) (5) However, these processes can also be administratively burdensome for states. (4) Any use of the new flexibilities — either administratively or through legislation — would be defined exclusively by the state without having to conform to existing federal approval and reporting processes.

TennCare’s proposed flexibilities fit into three buckets.

- The draft proposes to tap existing flexibilities to change benefits — but without the formal federal oversight and approval currently required. For example, TennCare would like the ability to modify both the coverage of optional benefits and details of other covered benefits (e.g. how much is covered and for how long) without federal approval.

Other examples include tailoring benefits to specific enrollee groups, offering non-health care benefits not traditionally covered by Medicaid (e.g. nutrition assistance), modifying enrollment processes, and changing the criteria for payments to hospitals for uncompensated care costs.

- The proposal includes new flexibilities not currently offered by federal law or regulation. Examples include instituting a drug formulary, funding broad public health initiatives, supporting technology adoption in rural areas, and instituting lock-out periods or benefit sanctions for enrollees found guilty of defrauding the program. It also pitches the idea of allowing a longer or even permanent approval period for the TennCare waiver.

- The draft includes exemptions from federal oversight requirements. TennCare is primarily asking to be exempt from federal regulations of Medicaid managed care programs. For example, these regulations require that states get federal approval of contracts and payment rates with managed care organizations (MCOs) ahead of time, maintain an MCO enrollee appeals process, and offer an MCO quality rating system.

The proposal does not appear to include any changes that would affect eligibility. TennCare would have to go through the normal CMS approval process to expand or shrink eligibility. If TennCare were to ask to add new populations in the future, they would be separate from the federal funding allotment until costs become predictable.

The proposed changes could have significant effects on TennCare spending, enrollees, and providers — either positive, negative, or mixed depending on if and how current or future state officials use that power. The proposal gives examples of how some of the flexibilities might be applied (e.g. to test pilot programs without federal approval), but it does not specify when or how state policymakers would use them. Without these details, there are few limits on the range of possible outcomes.

The draft in its current form does not specify if and how the program might report on its use of these flexibilities and their impact. There are no rules for how TennCare would notify CMS, affected stakeholders, or the public when state officials decide to use these new powers. While TennCare proposes tracking expenditures and measures around access to care and health outcomes for the entire waiver, the draft does not say how TennCare might monitor, evaluate, and share findings on the effects of using specific flexibilities.

TennCare’s recent record of instituting significant changes has had mixed results. In some circumstances, TennCare has been cited as a national leader in innovative payment and benefit models (e.g. value-based purchasing for behavioral health). (6) (7) (8) (9) In other cases, it has been criticized for how it has handled the implementation of major administrative changes (e.g. eligibility redetermination) and the monitoring of new initiatives (e.g. episodes of care). (10) (11)

3. How does the proposal change federal funding?

Under the proposal, federal funding for most TennCare enrollees’ medical costs would be capped. Today, the federal government pays 65% of TennCare’s costs, and the state pays the remaining 35% (subject to the limitations discussed in question four). This 65-35 arrangement would be replaced by a fixed federal funding allotment for the affected enrollees/spending. Under the proposal, Tennessee would be responsible for 100% of any spending above the new federal allotment but could use part of any savings from spending less than the allotment without a state match requirement (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Key details of the federal funding allotment include:

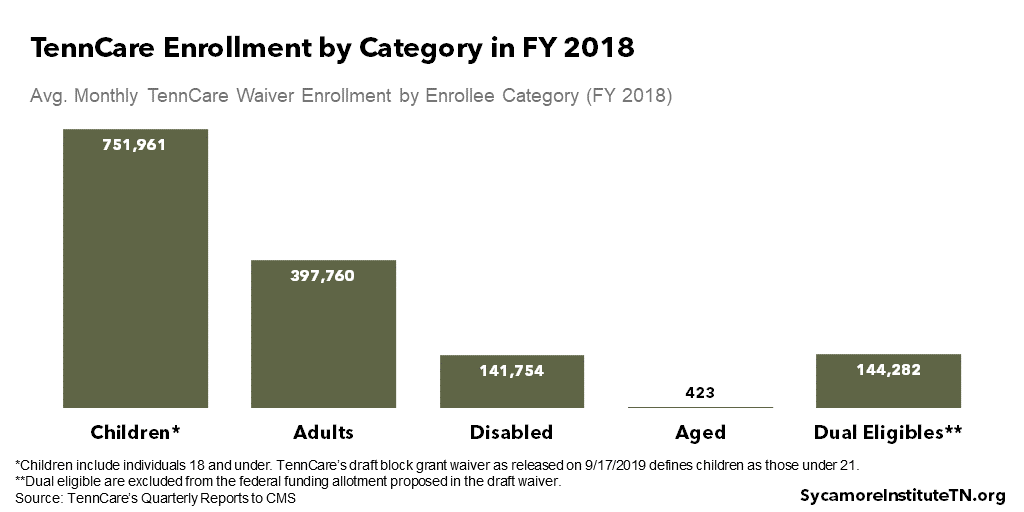

- Enrollee-Specific Per Capita Caps: TennCare’s federal funding allotment would be based on per capita amounts for four enrollee groups — children, adults, individuals with disabilities, and the elderly. Figure 2 shows average monthly enrollment across all five TennCare waiver groups in FY 2018. (12) The allotment would not apply to individuals eligible for both Medicare and TennCare (“dual eligibles”) or enrollees outside the main TennCare waiver (e.g. DIDD waivers).

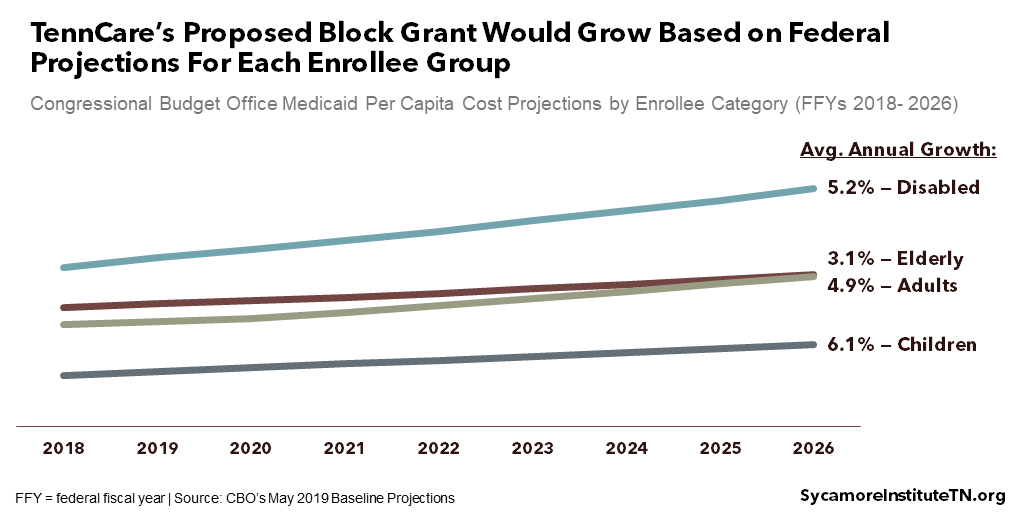

- Enrollee-Specific Cost Projections: Each year, the per capita costs would grow by the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projected rates for each of the four enrollee groups (Figure 3). (13)

- Enrollment: The federal funding allotment would be based on the higher of two metrics, either actual enrollment or enrollment in FYs 2016-2018 (i.e. “the base period”).

- Exclusions: Pharmaceutical costs, administrative costs, and supplemental payments for hospitals (e.g. for training physicians, uncompensated care) are all excluded from the allotment.

Figure 3

- State Maintenance of Effort: The state could use the allotment to reduce its share of costs for the affected enrollees/spending below the current 35% as long as state spending does not fall below a “maintenance of effort” (MOE) level. This state spending floor would be based on FY 2019 expenditures. The details of this calculation are not specified.

- Shared Savings: If TennCare does not spend the full federal allotment, Tennessee would be able to use 50% of those savings without any state match requirement. The waiver is not specific on how the funds could be used, but the supporting documents suggest they would be spent on “health-related services.”

- Time-Limited (or Permanent?): The proposal amends the current TennCare waiver. Waivers typically last for three to five years, which would allow the state and federal government to periodically revisit the proposal. Waivers can be extended many times. In fact, the current waiver (which expires on June 30, 2021) is an extension of the “TennCare II” waiver that was first approved by the federal government in 2002. However, the draft also proposes that the federal government consider making Tennessee’s waiver permanent or extending the period beyond the typical five years.

4. How does TennCare’s funding work now?

The proposal builds on some of the financial concepts already at work in TennCare. Because TennCare operates under a waiver, it must meet federal “budget neutrality” requirements. In other words, a state waiver cannot cost the federal government any more than it would be expected to spend in the absence of the waiver.

Similar to this proposal, the current budget neutrality requirement creates a federal funding ceiling based on enrollee-specific per capita caps, cost projections, and actual enrollment. (14) The existing base per capita caps were established under the initial TennCare II waiver in 2002. Since then, the caps have increased in line with federal projections for Medicaid growth nationwide. CMS has also allowed savings (i.e. the difference between actual spending and the budget neutrality cap) from one waiver period to roll-over into subsequent extension periods. If a state exceeds its total budget neutrality ceiling after accounting for any rollover savings, it must repay the excess amount to the federal government. (15)

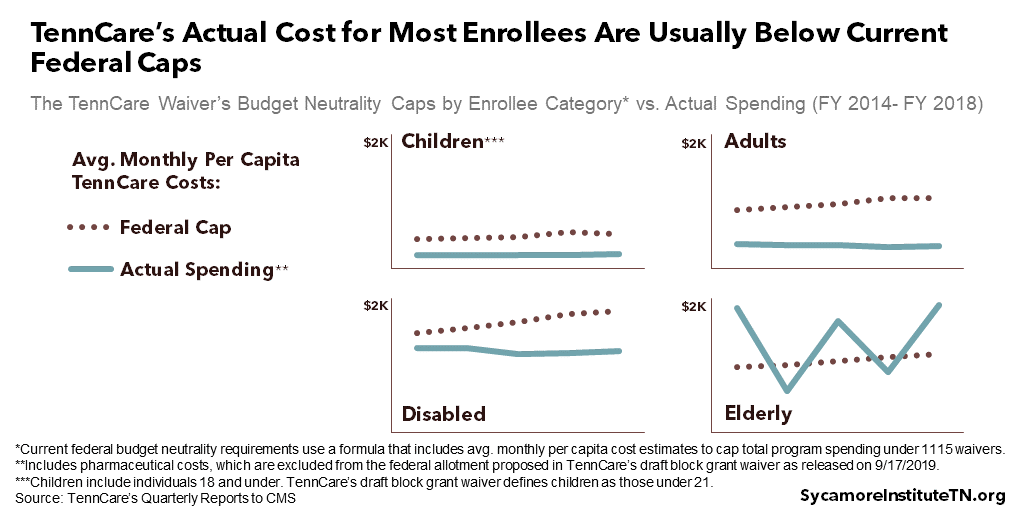

TennCare has consistently remained below its total budget neutrality ceiling. Between 2003 and 2021, TennCare predicts the program will cumulatively spend $31 billion less than the federal budget neutrality caps. (16) Figure 4 shows TennCare’s average annual per capita costs for each enrollee category since FY 2014 alongside the federal caps. (12)

Figure 4

5. What is Tennessee’s financial risk under the proposal?

By design, any fixed federal funding allotment comes with financial risk that could present trade-offs for state policymakers. Any downward pressure on federal TennCare funding might require state policymakers to balance the budget by making changes to TennCare, shifting money from other priorities, and/or raising taxes. All of these decisions would pose trade-offs.

The formula that would set the allotment, as currently proposed, is heavily weighted in Tennessee’s favor — at least in the short-term. Both the details of each variable and how those details interact matter. Below, we outline how the proposal deals with some of the critical details that determine the state’s financial risk.

- Base Amount: TennCare proposes an FY 2018 base of $7.9 billion, which would be adjusted each year based on the parameters discussed above and below. For context, Tennessee received $7.0 billion in total federal funding in FY 2018 for all TennCare expenses, not just those proposed for inclusion in the allotment.

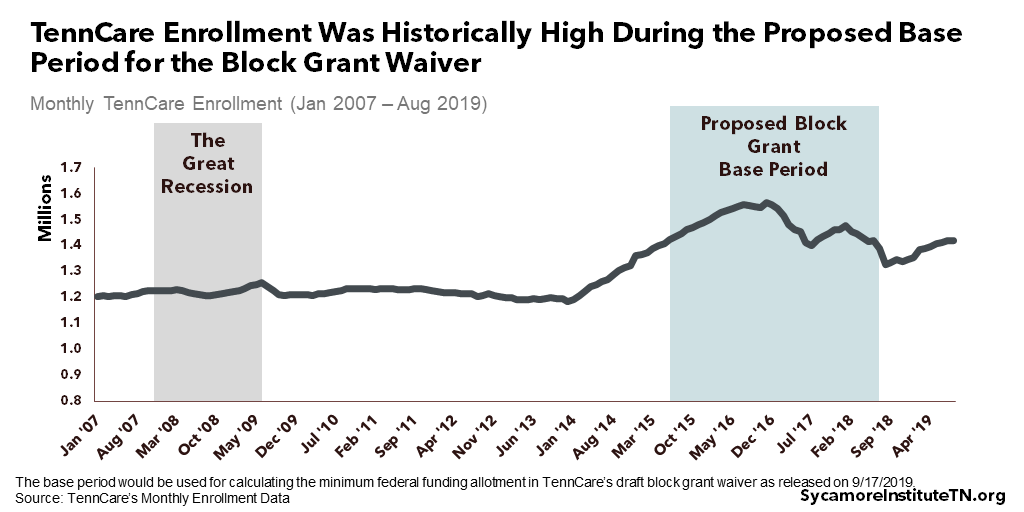

- Adjustments for Enrollment: TennCare enrollment during FYs 2016-2018 would be used to set a floor for the federal funding allotment. Enrollment during this base period was historically high (Figure 5) — even compared to the last recession. The allotment could be adjusted upward for changes in both overall enrollment and the mix of enrollee types. For example, the allotment would grow if a recession increased enrollment over the base period. It would also account for changes in the number of enrollees across each category even if overall enrollment remained stable.

Figure 5

- Accounting for Enrollee Differences: The proposed allotment accounts for nominal differences in spending patterns across the four different enrollee groups and differences in projected cost trends (Figure 3).

- Per Capita Caps: The proposed allotment base uses the FY 2018 per capita caps from TennCare’s existing budget neutrality ceiling. TennCare’s average costs for most enrollees was well below these caps (Figure 4), which largely reflect estimates of national enrollee costs in the absence of a waiver. Beginning in 2021, however, CMS plans to “rebase” states’ caps according to each state’s recent experience, instead of national trends. (15) This is expected to reduce Tennessee’s per capita caps under budget neutrality. It is unclear how CMS might weigh its new policy against TennCare’s proposal.

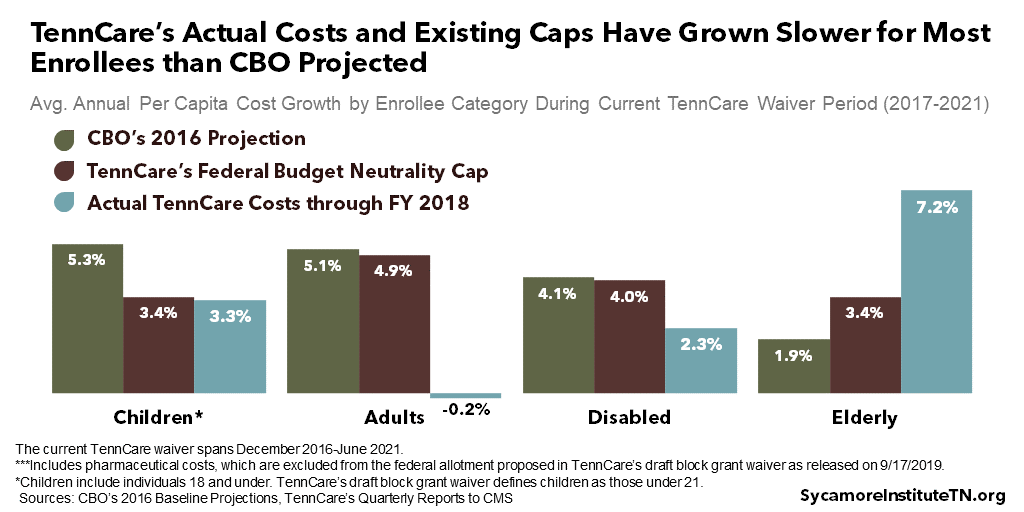

- National Medicaid Growth Trends: The draft proposal would grow each per capita cap using CBO trend projections. In recent history, TennCare’s actual costs and existing caps have grown slower than CBO projected for children, adults, and individuals with disabilities (Figure 6).

Figure 6

6. What happens next?

The public will have two chances to comment on this proposal before a decision by federal regulators, and the General Assembly must approve any final agreement before it takes effect.

- TennCare’s release of its draft waiver kicks off a 30-day public comment period that will end on October 18, 2019. During this time, TennCare will also hold three public forums across the state.

- Under the 2019 law, TennCare must submit a revised draft to CMS by November 20, 2019. CMS will publish the submission and hold its own 30-day public comment period. Federal rules require CMS to wait at least 45 days total after publishing the waiver before it can be approved. Most state-federal negotiations over Medicaid waivers take much longer than that. (19)

- Tennessee’s General Assembly must approve any final agreement between the Lee administration and federal regulators before it could be implemented. (2)

7. What are the chances federal regulators approve this?

These are relatively uncharted waters, so it is impossible to say. Here’s what we do know…

The Trump administration appears motivated to approve an ambitious state Medicaid reform with broader state flexibilities. (20) However, there is little precedent for the kinds of changes in the current proposal, and some less ambitious proposals by states like Kansas and Massachusetts have been rejected recently. (21)

Even if CMS and state lawmakers approve something along these lines, it is likely to face legal challenges that may ultimately halt implementation. The proposal would require significant deviations from previous interpretations of federal law and regulation, which will likely invite lawsuits. For example, many experts believe federal law does not allow the use of the waiver process to override the matching system that dictates Tennessee’s 65-35 split. (21) (22) (3) However, it is possible that the proposal is or could be structured to meet the technical funding requirements of federal law.

References

Click to Open/Close

- TennCare. Draft of Amendment 42 to the TennCare II Demonstration. September 17, 2019. Obtained from https://www.tn.gov/tenncare/policy-guidelines/waiver-and-state-plan-public-notices.html.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 481 (2019). May 24, 2019. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/111/pub/pc0481.pdf.

- United States of America. Section 1115 of the Social Security Act. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title11/1115.htm.

- Brian Neal. CMCS Informational Bulletin: Section 1115 Demonstration Process Improvements. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services. November 6, 2017. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib110617.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 1115 Demonstration State Monitoring & Evaluation Resources. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/evaluation-reports/evaluation-designs-and-reports/index.html.

- Soper, Michelle Herman, Matulis, Rachael and Menschner, Christopher. Moving Toward Value-Based Payment for Medicaid Behavioral Health Services. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc. June 2017. https://www.chcs.org/media/VBP-BH-Brief-061917.pdf.

- Smith, Derica and Hanlon, Carrie. Case Study: Tennessee’s Perinatal Episode of Care Payment Strategy Promotes Improved Birth Outcomes. National Academy for State Health Policy and the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality. October 2017. https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Tennessee-Case-Study.pdf.

- Spencer, Anna and Crawford, Maia. Promising State Innovation Model Approaches for High-Priority Medicaid Populations: Three State Case Studies. Center fo Health Care Strategies, Inc. March 2019. https://www.chcs.org/media/Promising-State-Innovation-Model-Approaches.pdf.

- Honsberger, Kate and Hanlon, Carrie. Tennessee: Using Managed Care Incentives to Improve Preventive Services and Care for Children. National Academy for State Health Policy. January 2018. https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Tennessee-Case-Study-2018.pdf.

- Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. Review of TennCare Eligiblity Redeteriminations. December 6, 2017. https://comptroller.tn.gov/content/dam/cot/sa/advanced-search/2017/tenncarememoandreport.pdf.

- —. Performance Audit Report: Division of TennCare. [Online] December 2018. https://comptroller.tn.gov/content/dam/cot/sa/advanced-search/2018/pa18043.pdf.

- TennCare. Quarterly Reports to the Federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2013-2019. Obtained from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/demonstration-and-waiver-list/?entry=8387.

- Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Medicaid—CBO’s May 2019 Baseline. May 2019. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-05/51301-2019-05-medicaid.pdf.

- TennCare. TennCare 1115 Demonstration Agreement with CMS. July 2, 2019. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents/tenncarewaiver.pdf.

- Hill, Timothy B. SMD # 18-009 RE: Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services. August 22, 2018. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd18009.pdf.

- TennCare. Appendix B: Anticipated Impact on Budget Neutrality. Draft of TennCare II Demonstration: Amendment 41. September 9, 2019. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/Amendment41.pdf.

- —. Monthly Enrollment Data. 2013-2019. Obtained from https://www.tn.gov/tenncare/information-statistics/enrollment-data.html.

- Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Detail of Spending and Enrollment for Medicaid for CBO’s March 2016 Baseline. March 2016. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/recurringdata/51301-2016-03-medicaid.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 42 CFR Part 431. February 27, 2012. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2012-02-27/html/2012-4354.htm.

- Verma, Seema. Speech: Remarks by Administrator Seema Verma at the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD) 2017 Fall Conference. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. November 7, 2017. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/speech-remarks-administrator-seema-verma-national-association-medicaid-directors-namd-2017-fall.

- Hinton, Elizabeth, et al. Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: The Current Landscape of Approved and Pending Waivers. Kaiser Family Foundation. February 12, 2019. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/section-1115-medicaid-demonstration-waivers-the-current-landscape-of-approved-and-pending-waivers.

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Medicaid 101: Waivers. https://www.macpac.gov/medicaid-101/waivers/.

Featured image by Direct Relief

*Updated on 9/23/2019 to correct a typo in Figure 2. The “disabled” category was incorrectly labeled as “aged.”